Macaw feathers

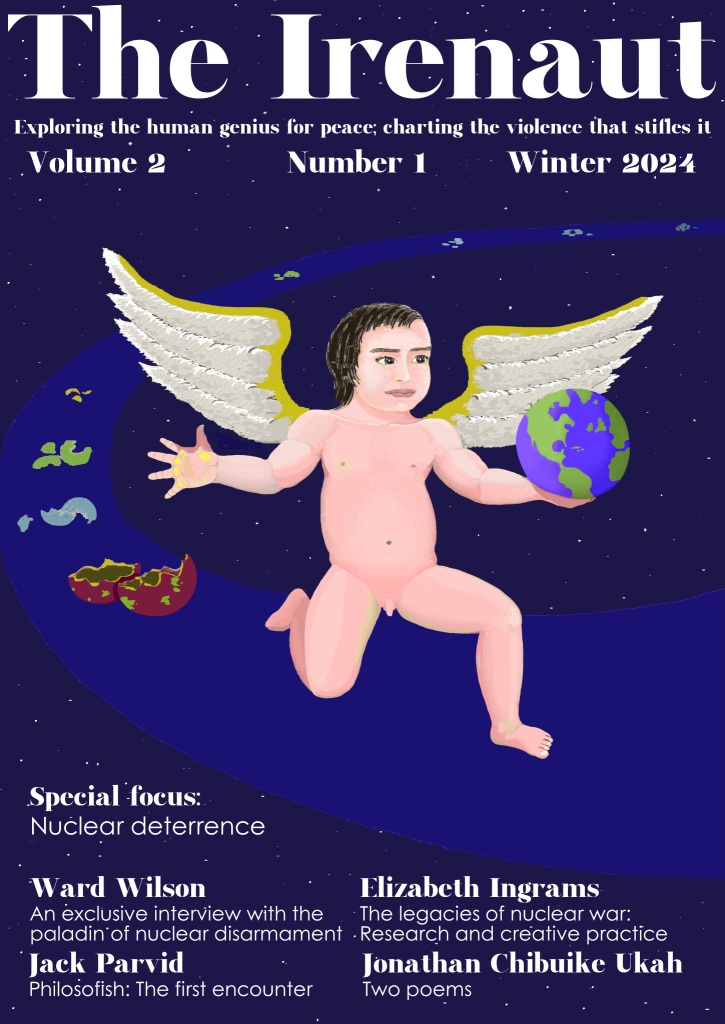

As the Homeric warrior virtues palled on the classical world, comfortless Hades yielded to blissful Elysium, and depictions of Thanatos, the personification of death, changed from a stern-faced, sword-bearing youth to a smiling cherub—rather like Cupid—signalling a life quenched with his downward pointing torch. No aspect of our lives is completely untouched by death, so it’s unsurprising that its meaning changes and demands fresh representations.

But how shall we depict Thanatos today, speeding faceless from the sky, if the entire biosphere becomes his quarry? Perhaps traumatised survivors will carve the features of our leaders into necrotic trees while their children, groping for an iconography of world-death, trace images of monsters in the radioactive dust. And as the nuclear winter bites, with what tokens of our culture shall we surround ourselves? What last, anguished meanings will our music, poetry, painting give us, before meaning itself is lost? For the ultimate terror of nuclear war, from which its symbolic power is derived, is its power to end meaning. Loss-in-the-world is harrowingly documented day after day: loss of loved ones, loss of freedom, loss of hope. But loss-of-world is by its nature silent, has no phenomenology.

The closest impression we have is the ‘Man of the Hole’. We don’t know what language he spoke. His name and the name of his people are unrecorded. Sole survivor of a genocide by settlers in the Brazilian Amazonian forest, he lived many years alone on his tribe’s ancestral lands, and died, still alone, in 2022. Feeling death close in—his own death and with it the memory of his people—he carefully surrounded himself where he lay with macaw feathers. The vital significance they had for him is lost to us, but his efforts to keep meaning alive as he lived and worked in solitude, digging the mysterious holes from which the name we gave him derives, must have been as arduous as any of the glorious homicides Homer’s warriors enacted in the fields of Troy.

While his people still lived, their understanding refracted the meanings of his encounters with the world, and he would, as we do, take ever more subtle paths to shade his knowledge into theirs, borrowing perspectives, rounding out bare glimpses. When they were gone, the unshared meanings of his solitude were his world’s last traces, the plumage of its extinction. For a few years, we peered at him from a safe distance, uncomprehending, through the trees. He warned us off and worked steadily to sublate those last traces into his post-apocalyptic culture and finally, when he died, baffled us with its dumb symbols.

And yet, how could we not understand him? Why else does his life move us to empathy? Infinitely refracted experiences of the world (compelling us to invent and reinvent Thanatos, along with all our other representations) are not chaotic: they emerge from forms of life, not from a junkyard tornado. Forms of life, engendered by our common need to survive and flourish, weave our symbols and imaginaries; and the irenic force, which links survival and flourishing—the origin and purpose of all human effort—is the loom on which the tribesman’s meanings and our own are stretched. This is why and how we understand him. And through understanding him we also know that if we ever face nuclear war—the apotheosis of violence, the antithesis of survival and flourishing—then the time will come to surround ourselves with the solace of our music and poetry, and with the memory of our present hopes for a better, fairer future for humanity. And then these things will be our macaw feathers.

* * * *

This offering includes the work of several contributors to the First Interdisciplinary Nuclear Disarmament Symposium at the University of Bradford, which I attended in December 2024. Bradford’s Department of Peace Studies deserves its international prestige: full of talent and creativity, lecturers and students alike exude a palpable commitment to the vital cause of peace. This issue of The Irenaut was meant to showcase the breadth and depth of the symposium, and the work of all the scholars present, but for reasons I have not yet completely understood, our original project was derailed. Personality clashes occur even in peace departments!

Nonetheless, we have a fine selection of the symposiasts’ work, an essay by Ward Wilson and an interview with him, beautiful poems by N. S. Thompson and Jonathan Chibuike Ukah, a new story from Jack Parvid in which he describes his first encounter with the misanthropic sardine, and an extraordinary photo essay by Andrew Thomas.

Thank you to our contributors for their inspiring work, and to you, our readers, for your commitment to The Irenaut, even when an issue is long overdue. We are working to get our next issue out early in July.

Mark-Alec Mellor