Animals and plants flourish according to their nature. A strong and vigorous lion is a flourishing lion, no matter how other lions are faring. Even in a wilderness, a single flower that grows and blossoms is a thriving flower. But human flourishing is problematic. It has an ethical dimension. I’ll briefly explore this, before describing the striking divergence between how Western industrialised societies and Indigenous communities experience the ethics of flourishing.

Why is flourishing problematic for humans? In his The Theory of Moral Sentiments, Adam Smith asks, ‘What can be added to the happiness of the man who is in health, who is out of debt, and has a clear conscience?’ Smith was making a point about the psychology of empathy, which some authors who cite him don’t mention, preferring to take his remark as a kind of no-nonsense view of human happiness. But even if we understand happiness to denote merely a psychological state, this is a dismally low baseline— bereft of music, literature, art, and reflection. Worse, the picture completely fails to include our relationships with others, contradicting what we know empirically about human happiness, which depends so much on other people, as many studies have confirmed, including the eight-decades-long Harvard Study of Adult Development. And even at this psychological level, how could I enjoy being well-nourished and solvent and mentally untroubled (to use Smith’s indices) among starving, indigent, suffering fellow humans? We just didn’t evolve that way.

However, there is a more radical inadequacy in this account of happiness, if we take it to mean flourishing in a fuller sense. For most of us, the idea of thriving in the midst of misery is repugnant. How could we justify our felicity in a society whose other members lack the basic components of well-being? Could I skip down the street rejoicing in my blissful life while my fellow citizens groan in anguish and pain all around me? We would regard an individual’s ‘flourishing’ in this milieu as grotesque, even if she were not prospering at the expense of others, through slavery, for example.

For humans, then, there is at least an intimation of an ethical question to be asked about flourishing. However we define it, we don’t achieve flourishing with a specific part of ourselves: I can be super fit, brilliant at maths, have a marvellous love life, be a virtuoso pianist, and still feel there is something lacking, without which I cannot truly thrive. We flourish as a whole, or not at all. A flower with healthy leaves but blighted petals isn’t flourishing. Therefore, we—standing inescapably in an ethical relation to the world and to others—cannot flourish in exclusive pursuit of self-fulfilment. Failure to acknowledge our place in a shared world, and that our actions—or inaction—affect others, diminishes us below the threshold required for flourishing as a whole person.

Turning again to the question of suffering, I said above that the idea of thriving in the midst of misery would seem repugnant. But what counts as ‘in the midst’? It seems obvious at the level of the family or the tribe, where we are intimately engaged with and routinely responsive to those around us, but as we scale up, even to city level, the moral exigency fades and our ethical engagement weakens. At global level, it barely exists, although we may, with donations to charity for example, contrive to assuage our feelings of unease at media reports of distant horrors. We are no longer ‘in the midst’ of people who suffer thousands of miles away. And yet, as Peter Singer argues in ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’, geographical distance does not exempt us from our moral obligations to help others.

We might agree with Singer, but it’s important to understand that he’s invoking a universal sense of duty that springs from a detached beholding, an autonomous moral reckoning, an orphaned conscience. This universalism is already present in the Pauline idea of a moral code written on the heart by a deity, and which applies to everyone (‘There is neither Jew nor Greek, there is neither slave nor free, there is no male or female…’). It is the perfect ethics for empires, for multi-national corporations, for religions, for capitalism, for socialism, for anyone who feels part of a planet-wide family, for a fragmented society. It was transformed by Kant into a rational principle that is the apotheosis of Enlightenment ethics, but retains the key feature of deontic autonomy: For Paul, I see what my duty is by looking into my heart (conscience); in Kant’s secular version, I see what my duty is by aligning it with a universal categorical imperative. For Paul, autonomy is guaranteed by our private access to the moral code; for Kant, by every human’s rationality.

It’s hard to see how citizens of industrialised societies could possibly have any other ethical perspective when they look out at the wider world. When we created empires, subjugating people we didn’t understand, claiming lands to which we had no attachment; when our ingenuity, enthusiasm and brutality made the world our panopticon, we needed such an ethics to govern our relationship with the (for us) inscrutable reality we had burst in upon, and to justify what we did there. We proclaimed universal human rights and equality for all, thus massively over-extending our moral jurisdiction over intricate traditions, social arrangements, and ways of relating to an environment. Paradoxically, moral conscience, the jewel of our hard-won individualism, is what legitimised our proffered universal embrace. We entered other lands fully armed with duties formed in the crucible of an inward gaze.

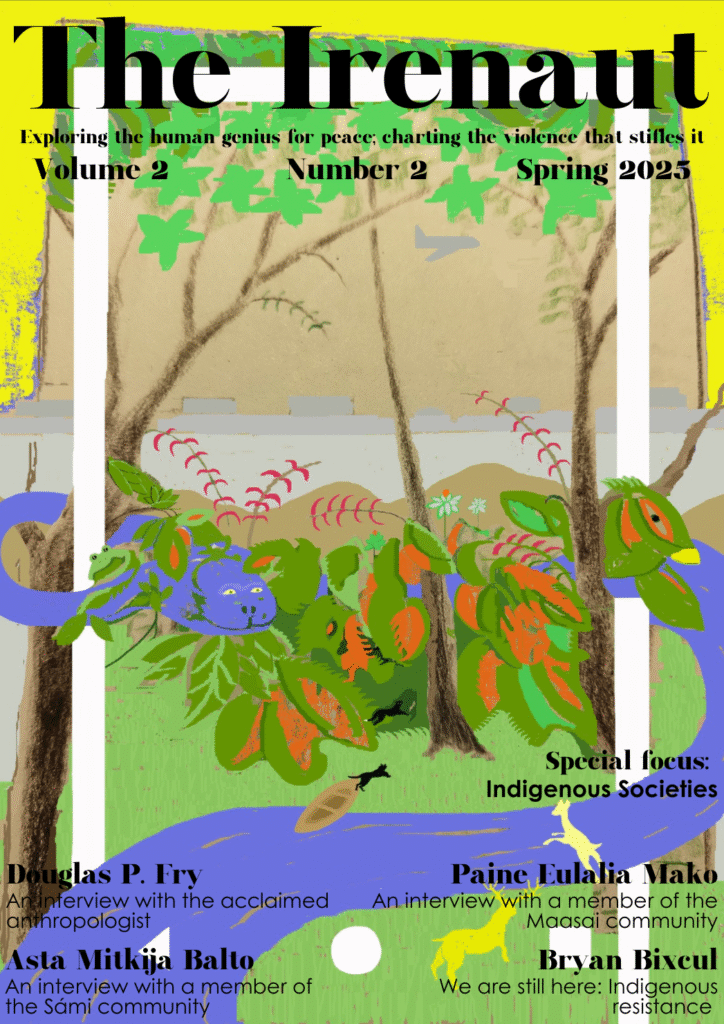

Speaking to people from Indigenous communities for this issue of The Irenaut and reading their contributions, I heard a different account of duty. The natural world that surrounds me and from which I get my sustenance summons me to engage with it to survive and flourish. If I fail to respond to this call, I, along with my community, will perish. It makes no sense to turn my gaze inwards to find out what I ought to do, when my world is clearly instructing me. This chimes with our own small-scale sense of duty: I don’t have to scrutinise my conscience before giving water to my thirsty dog; if my neighbour’s house is on fire, I don’t look deep into my soul to discover the truth about whether I ought to call the fire brigade. We might say with Sartre (replacing values with duties) ‘The immediate is the world with its urgency, and in this world where I engage myself, my acts cause duties to spring up like partridges’. Many Indigenous communities have managed to extend this dutifulness sensitively and knowledgeably to their entire world, always seeking a harmony sustained by a minute and panoramic attentiveness to others and to their environment.

To give a name to this experience of obligation, where duties are drawn out from us by our engagement with the world, l call it deontic eduction. Can we find a way to combine deontic eduction with a universal conception of flourishing? That would be the only way to bring about a genuine global dutifulness. We’re seeing the beginnings of this in our—still inchoate and disputed—efforts to mitigate the effects of industry on our planet, in our recognition of the evils of colonisation, and in our attunement to diverse voices and interests. Gradually, we are realising that duties, which can be asserted in a brief statement, must answer to survival needs that require lengthy testaments and life stories. Unless our actions arise as duties educed from us amid a given environment, we have no business there, and should leave it to those who are roused to deploy creative jeopardy to reconnect survival with flourishing, and thus allow the irenic force its full power.

Mark-Alec Mellor